Every day more than 1.8 million books are sold in the US and another half a million books are sold in the UK. Despite all the other easy distractions available to us today, there’s no doubt that many people still love reading. Books can teach us plenty about the world, of course, as well as improving our vocabularies and writing skills. But can fiction also make us better people?

The claims for fiction are great. It’s been credited with everything from an increase in volunteering and charitable giving to the tendency to vote – and even with the gradual decrease in violence over the centuries.

Characters hook us into stories. Aristotle said that when we watch a tragedy two emotions predominate: pity (for the character) and fear (for yourself). Without necessarily even noticing, we imagine what it’s like to be them and compare their reactions to situations with how we responded in the past, or imagine we might in the future.

This exercise in perspective-taking is like a training course in understanding others. The Canadian cognitive psychologist Keith Oatley calls fiction “the mind’s flight simulator”. Just as pilots can practise flying without leaving the ground, people who read fiction may improve their social skills each time they open a novel. In his research, he has found that as we begin to identify with the characters, we start to consider their goals and desires instead of our own. When they are in danger, our hearts start to race. We might even gasp. But we read with luxury of knowing that none of this is happening to us. We don’t wet ourselves with terror or jump out of windows to escape.

Having said that, some of the neural mechanisms the brain uses to make sense of narratives in stories do share similarities with those used in real-life situations. If we read the word “kick”, for example, areas of the brain related to physically kicking are activated. If we read that a character pulled a light cord, activity increases in the region of the brain associated with grasping.

To follow a plot, we need to know who knows what, how they feel about it and what each character believes others might be thinking. This requires the skill known as “theory of mind”. When people read about a character’s thoughts, areas of the brain associated with theory of mind are activated.

When people read about a character’s thoughts, areas of the brain associated with theory of mind are activated (Credit: Getty Images)

With all this practise in empathising with other people through reading, you would think it would be possible to demonstrate that those who read fiction have better social skills than those who read mostly non-fiction or don’t read at all.

The difficulty with conducting this kind of research is that many of us have a tendency to exaggerate the number of books we’ve read. To get around this, Oatley and colleagues gave students a list of fiction and non-fiction writers and asked them to indicate which writers they had heard of. They warned them that a few fake names had been thrown in to check they weren’t lying. The number of writers people have heard of turns out to be a good proxy for how much they actually read.

Many of us tend to exaggerate the number of books we’ve read (Credit: Getty Images)

Next, Oatley’s team gave people the “Mind in the Eyes” test, where you are given a series of photographs of pairs of eyes. From the eyes and surrounding skin alone, your task is to divine which emotion a person is feeling. You are given a short list of options like shy, guilty, daydreaming or worried. The expressions are subtle and at first glance might appear neutral, so it’s harder than it sounds. But those deemed to have read more fiction than non-fiction scored higher on this test – as well as on a scale measuring interpersonal sensitivity.

At the Princeton Social Neuroscience Lab, psychologist Diana Tamir has demonstrated that people who often read fiction have better social cognition. In other words, they’re more skilled at working out what other people are thinking and feeling. Using brain scans, she has found that while reading fiction, there is more activity in parts of the default mode network of the brain that are involved in simulating what other people are thinking.

People who often read fiction have greater social cognition (Credit: Getty Images)

People who read novels appear to be better than average at reading other people’s emotions, but does that necessarily make them better people? To test this, researchers at used a method many a psychology student has tried at some point, where you “accidentally” drop a bunch of pens on the floor and then see who offers to help you gather them up. Before the pen-drop took place participants were given a mood questionnaire interspersed with questions measuring empathy. Then they read a short story and answered a series of questions about to the extent they had felt transported while reading the story. Did they have a vivid mental picture of the characters? Did they want to learn more about the characters after they’d finished the story?

The experimenters then said they needed to fetch something from another room and, oops, dropped six pens on the way out. It worked: the people who felt the most transported by the story and expressed the most empathy for the characters were more likely to help retrieve the pens.

You might be wondering whether the people who cared the most about the characters in the story were the kinder people in the first place – as in, the type of people who would offer to help others. But the authors of the study took into account people’s scores for empathy and found that, regardless, those who were most transported by the story behaved more altruistically.

In one experiment, people who felt most transported by a story later behaved more altruistically (Credit: Getty Images)

Of course, experiments are one thing. Before we extrapolate to wider society we need to be careful about the direction of causality. There is always the possibility that in real life, people who are more empathic in the first place are more interested in other people’s interior lives and that this interest draws them towards reading fiction. It’s not an easy topic to research: the ideal study would involving measuring people’s empathy levels, randomly allocating them either to read numerous novels or none at all for many years, and then measuring their empathy levels again to see whether reading novels had made any difference.

Instead, short-term studies have been done. For example, Dutch researchers arranged for students to read either newspaper articles about riots in Greece and liberation day in the Netherlands or the first chapter from Nobel Prize winner Jose Saramago’s novel Blindness. In this story, a man is waiting in his car at traffic lights when he suddenly goes blind. His passengers bring him home and a passer-by promises to drive his car home for him, but instead he steals it. When students read the story, not only did their empathy levels rise immediately afterwards, but provided they had felt emotionally transported by the story, a week later they scored even higher on empathy than they did right after reading.

Of course, you could argue that fiction isn’t alone in this. We can empathise with people we see in news stories too, and hopefully we often do. But fiction has at least three advantages. We have access to the character’s interior world in a way we normally do not with journalism, and we are more likely to willingly suspend disbelief without questioning the veracity of what people are saying. Finally, novels allow us to do something that is hard to do in our own lives, which is to view a character’s life over many years.

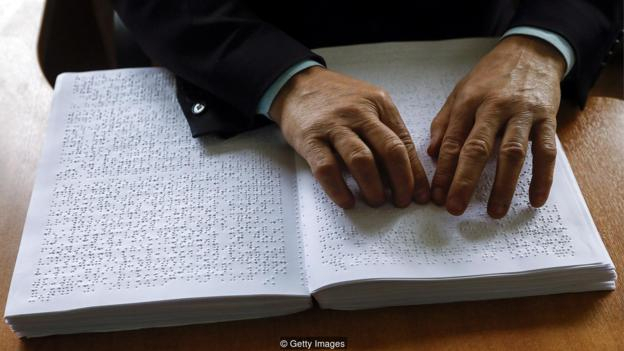

Some institutions consider reading to be so significant that they include modules on literature (Credit: Getty Images)

So the research shows that perhaps reading fiction does make people behave better. Certainly some institutions consider the effects of reading to be so significant that they now include modules on literature. At the University of California Irvine, for example, Johanna Shapiro from the Department of Family Medicine firmly believes that reading fiction results in better doctors and has led the establishment of a humanities programme to train medical students.

It sounds as though it’s time to lose the stereotype of the shy bookworm whose nose is always in a book because they find it difficult to deal with real people. In fact, these bookworms might be better than everyone else at understanding human beings.

BBC Future

More about: reading